Introduction — A hook from history

In the summer of 1858, London became almost unlivable. The River Thames, into which the city had been dumping its waste for centuries, turned into a rotting cesspool. The smell was so overpowering that Members of Parliament fled their chambers or sat with handkerchiefs soaked in lime and vinegar pressed to their noses. The newspapers called it the Great Stink, and the crisis was so severe that it forced the British state to act. Within years, Joseph Bazalgette’s revolutionary sewer system was under construction, setting the foundation for modern London’s sanitation.

Contrast this with today: London is a global capital admired for its cleanliness and infrastructure. Paris, once plagued by dark slums and epidemics, is now a tourist paradise of grand boulevards and sparkling riverbanks. Berlin, Amsterdam, and other European cities, once chaotic, overcrowded, and filthy, today rank among the most liveable cities in the world.

Now look at India. A rising economic power, a leader in IT and space technology, a country of over 1.4 billion people. Yet, Indian cities remain plagued by overflowing drains, uncollected garbage, smog-filled air, and unplanned growth. How can India—so full of potential—escape the same painful mistakes Europe made, but in a fraction of the time?

The answer lies not only in infrastructure but also in psychology and behavior. Europe’s clean streets and orderly systems are not cultural accidents. They were built out of crisis, blood, and reform. India, if it learns, can skip the blood and go straight to the reform.

India’s Current Urban Predicament

1. Sanitation: more toilets, but weak sewage

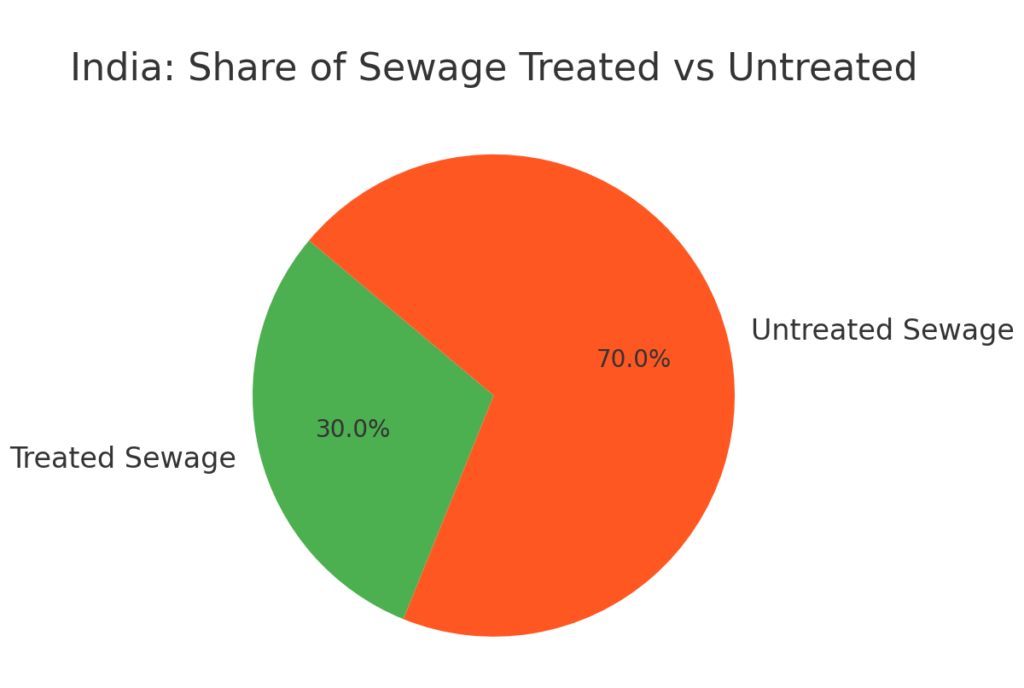

India has invested heavily in sanitation. The Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) built over 110 million toilets, aiming to end open defecation. Yet the challenge today is not the toilet but the sewer. According to the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), over 70% of sewage generated in urban India goes untreated. Much of it flows directly into rivers like the Yamuna and Ganga, turning them into toxic streams.

- In Delhi alone, the Yamuna receives untreated waste at 20 major drains, despite decades of cleaning projects.

- Smaller cities face even worse challenges, with almost no sewage treatment plants, leaving rivers to function as open drains.

In short, India has tackled one half of sanitation—access to toilets—but without functional sewage and waste treatment, the cycle remains broken.

2. Unplanned urban growth: cities growing faster than governance

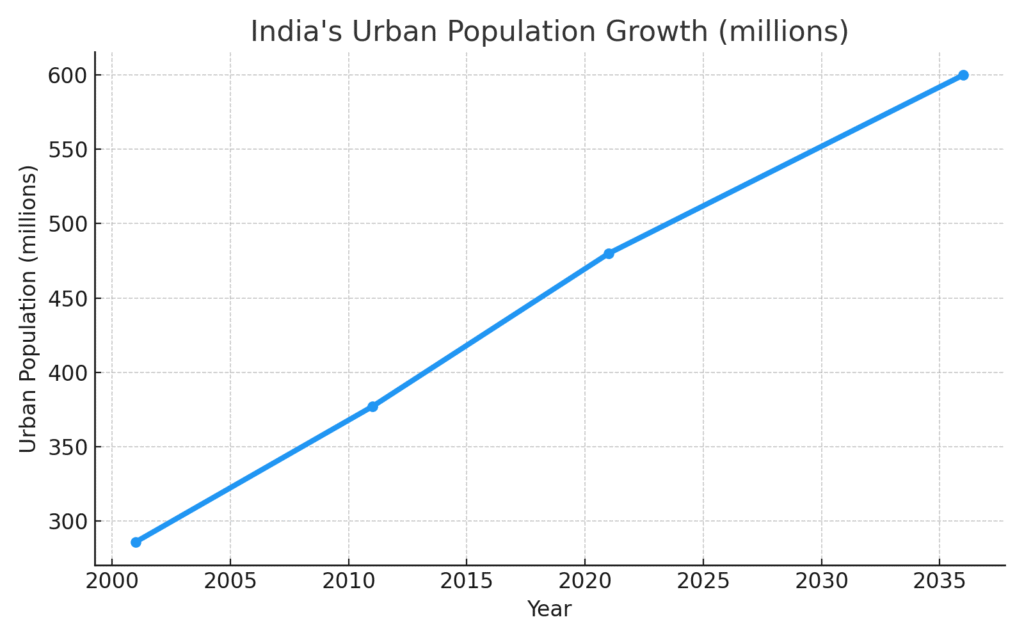

India’s urban population is projected to reach 600 million by 2036. Yet, most cities expand not by design but by sprawl. Private developers carve housing colonies before sewerage, drains, and solid waste systems are laid. Informal settlements mushroom without even the most basic services.

Examples:

- Gurgaon (Gurugram), India’s corporate hub, rose in two decades but still floods after short rains due to poor drainage.

- Bengaluru, once the “Garden City,” now faces a water crisis—its lakes foaming with chemicals and catching fire, while groundwater levels plummet.

- Mumbai, India’s financial capital, continues to rely on a colonial-era drainage system built in 1860. Monsoon floods paralyze the city each year, despite billions spent on upgrades.

The mismatch is simple: India’s urban planning capacity is inadequate. The country has fewer than 5,000 trained urban planners, while it needs at least 30,000 for its scale.

3. Pollution: Air you can chew, water you can’t drink

India’s pollution challenge is stark.

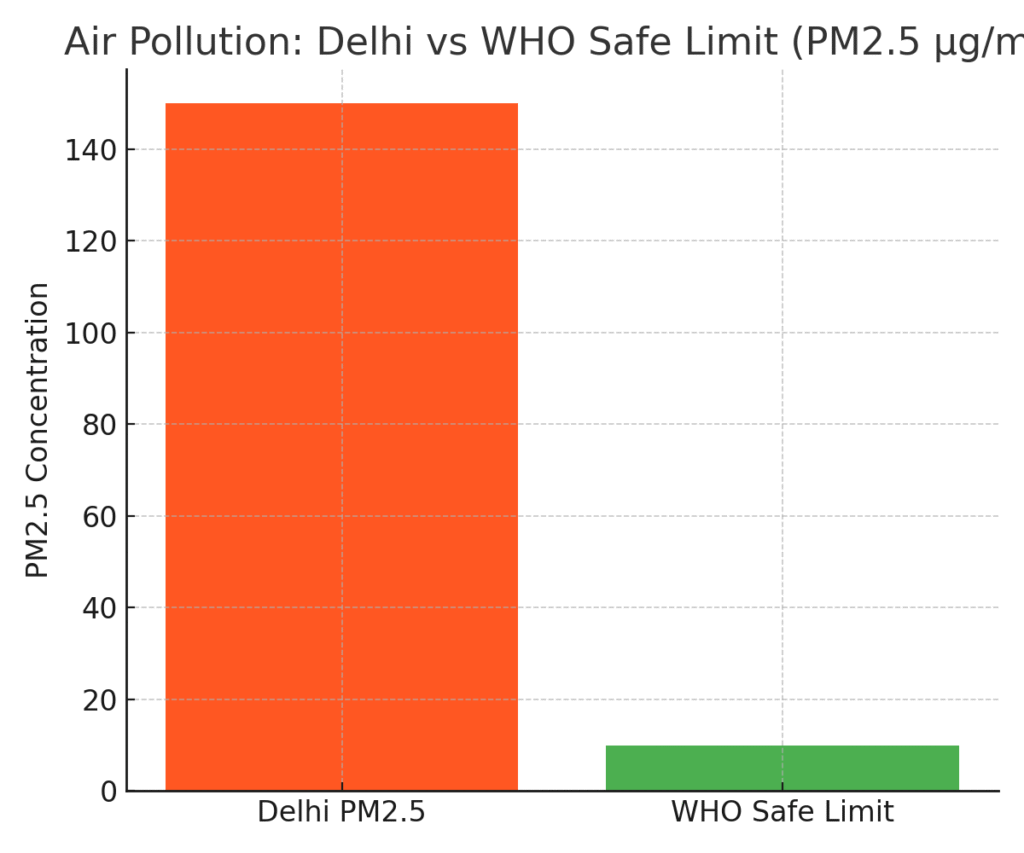

- Air: In 2023, Delhi’s PM2.5 level was over 15 times the WHO safe limit. According to the Lancet, air pollution contributed to over 1.6 million deaths in India in 2019.

- Water: CPCB reports that of India’s 351 river stretches monitored, more than half are polluted, primarily due to untreated sewage.

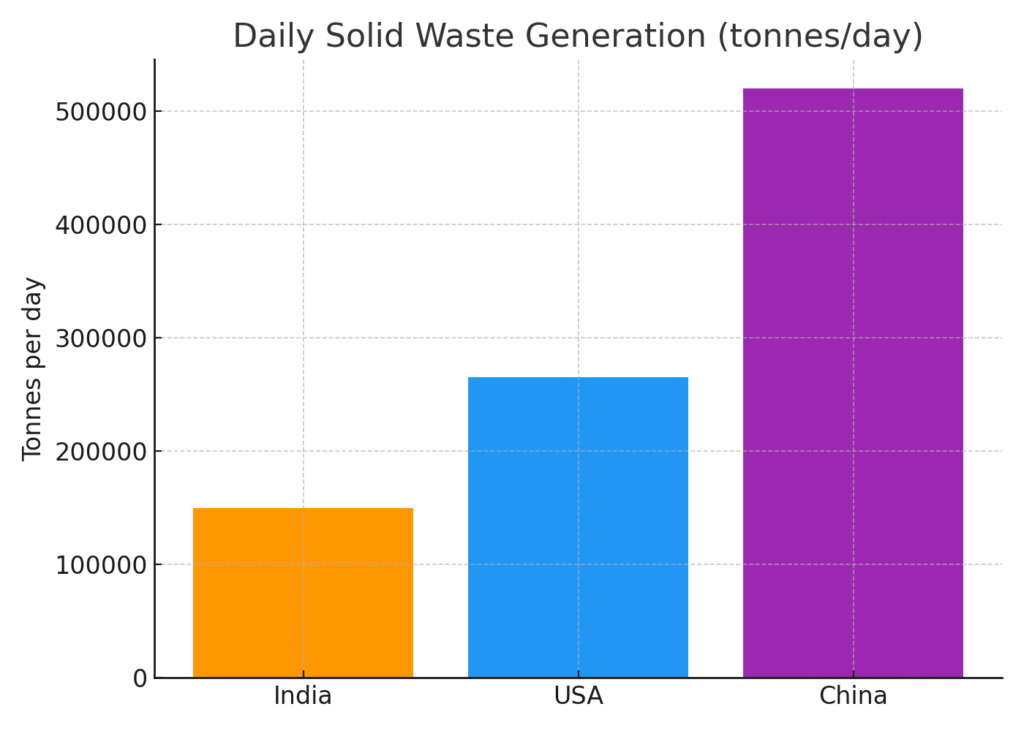

- Solid waste: India generates about 150,000 tonnes daily, yet segregation at source remains below 30%. Mega-landfills like Ghazipur in Delhi and Deonar in Mumbai are taller than many city buildings, smoldering and leaching toxins.

Europe was no different once. But while Europe acted, India is still inching toward solutions.

4. Behavioral inertia: the missing piece

Even where infrastructure exists, behavior undermines it. Public bins overflow because people dump mixed waste. Spitting and littering remain common. Vehicles idle with engines running. “Not in my backyard” thinking dominates—people keep their homes clean but treat streets as dumping grounds.

The truth is: India’s problem is not just lack of infrastructure, but a weak civic culture. Without behavioral change, drains will clog the day after they are cleaned.

Europe’s Filthy Past: Dirtier than India today

It is hard to imagine Paris, London, or Berlin as more chaotic and dirty than today’s Indian cities. Yet, 150 years ago, they were worse.

- London’s Great Stink (1858): Raw sewage flowed into the Thames. The smell was so strong it disrupted governance. Cholera outbreaks killed tens of thousands.

- Paris before Haussmann: In the 1840s, most Parisians lived in overcrowded, dark alleys. Epidemics like cholera killed over 18,000 people in 1832 alone. Waste disposal was haphazard, water unsafe.

- Berlin & Hamburg: German cities had “night soil men” carting human waste in barrels. Epidemics were frequent, and industrial smoke blackened the sky.

- Air pollution: By the late 19th century, London’s smogs turned day into night. In December 1952, the Great Smog killed an estimated 12,000 people in just a week.

In short, Europe’s cities were cesspools of disease, pollution, and chaos.

How Europe Turned the Corner

1. Law as a weapon

The turning point came when governments realized public health is governance.

- Britain’s Public Health Act (1848, 1875): Obligated local authorities to provide drains, sewers, clean water, and regulate new buildings. This was revolutionary—sanitation became a legal duty, not optional charity.

- France, Germany, and others followed with housing codes, sewer mandates, and industrial regulations.

2. Over-engineering for the future

- Joseph Bazalgette’s sewers (London): 1,100 miles of street sewers, 82 miles of intercepting sewers, and massive pumping stations. Crucially, Bazalgette built them double the size needed, predicting future growth. His foresight meant London’s sewers are still in use today.

- Paris under Haussmann: Boulevards were cut through slums, lined with trees, and underpinned by sewer and water networks. By 1878, Paris had 600 km of sewers, making epidemics less frequent.

3. Urban redesign

- Parks, wide roads, and zoning reduced crowding. Street lighting and police patrols made cities safer.

- Housing reforms reduced tenements and introduced ventilation and windows, cutting disease spread.

4. Behavioral revolutions

- Laws fined people for spitting, littering, and dumping waste.

- Schools taught hygiene as patriotism.

- Public campaigns reframed cleanliness as a sign of modernity.

- Paris even ran sewer tours to showcase progress—sanitation became a source of civic pride.

5. Science and data

- John Snow’s cholera map (1854): Proved cholera spread through contaminated water, not “bad air.”

- Louis Pasteur’s germ theory (1860s): Cemented the link between microbes and disease.

- Together, these scientific breakthroughs justified massive public investment in sanitation.

The Psychology of Cleanliness

Europe’s transformation was not just technical but psychological.

- Cleanliness = modernity: A clean city became a symbol of progress, attracting trade and prestige.

- Shame and pride: Dirty habits were stigmatized, while orderliness was rewarded with civic pride.

- Institutional reinforcement: Schools, laws, and urban design all nudged people toward cleaner behavior.

This cultural shift ensured reforms stuck.

Lessons for India

1. Treat sanitation as a full system, not piecemeal

- Toilets must connect to sewers or fecal sludge treatment.

- Rivers cannot remain dumping grounds.

- Example: Indore has become India’s cleanest city by integrating waste collection, segregation, and treatment, combined with public participation.

2. Plan ahead, not behind

- Urban planning must anticipate growth. Every new colony should be legally required to connect to sewerage, have waste contracts, and clear drainage before occupancy.

- Example: Ahmedabad’s riverfront project integrated flood management, sewage treatment, and public spaces—a proactive model.

3. Pollution laws with teeth

- The National Clean Air Programme aims to reduce PM2.5 by 40% by 2026. This must be enforced with strict industry compliance and incentives for clean fuels.

- Cities should emulate London’s congestion pricing and Paris’s low-emission zones to cut vehicle pollution.

4. Behavioral nudges that stick

- Bins at every corner, maintained daily.

- Ward rankings: Publish real-time dashboards so neighborhoods compete on cleanliness.

- Celebrate sanitation workers with public honors and visibility, turning them into heroes like Europe once did.

5. Transparency and accountability

- Ward-level dashboards of garbage pickup, drain cleaning, and PM2.5 levels.

- Pay contractors for verified outcomes, not paperwork.

6. Long-term vision

- Europe took 100 years to reform. India, with technology and global knowledge, can compress this into 15–20 years.

Conclusion — Skip the stink, seize the future

Europe’s clean, orderly cities were not born clean. They emerged from filth, epidemics, and even death. They cleaned up because they had no choice. India has a choice today: wait for a disaster like the Great Stink, or act now.

Sanitation, pollution control, and urban planning are not luxuries—they are prerequisites for dignity, health, and prosperity. Clean streets and rivers are not just about pride—they are about life expectancy, productivity, and human development.

If Europe could turn cesspools into tourist rivers and sewers into sources of civic pride, India—with its innovation and ambition—can do even better. The question is whether we act with the urgency of history.

References (selected)

- Great Stink & Bazalgette sewers (London): Wikipedia compendium with primary references; Museum of London overview. (Wikipedia, London Museum)

- John Snow & Broad Street pump (1854): CDC MMWR anniversary note (pump handle removal and dates). (CDC)

- Paris Haussmannization & sewers: Paris Sewer Museum and historical syntheses. (Wikipedia)

- Public Health Acts (UK): UK parliamentary and policy summaries (1848; 1875 consolidation and duties). (parliament.uk, Policy Navigator)

- Great Smog (1952) & Clean Air Act (1956): Britannica and GLA overviews. (Encyclopedia Britannica, London City Hall)

- India air quality & NCAP: IQAir summaries; peer-reviewed and NGO reviews of NCAP’s 40% by 2026 target. (IQAir, PMC, CRECA)

- Human development & life expectancy: UNDP HDI (India rank and value); long-run life expectancy series for Europe (France example). (UNDP, ined.fr)