Introduction

The Uttar Pradesh (UP) government has recently decided to merge or “pair” thousands of primary schools that have fewer than 50 students with nearby larger schools. This sweeping policy, upheld by the Allahabad High Court in 2025, affects over 10,000 of UP’s 1.3 lakh government-run primary schools. Officials argue that consolidating small, under-enrolled schools will pool resources, improve infrastructure, and align with the National Education Policy 2020’s vision of vibrant “neighborhood schools”.

However, the decision has sparked strong criticism from educators, parents, and activists, who fear it may do more harm than good. The poorest and most marginalized children could be hardest hit. For 8-year-old Amit in rural Lucknow, the merger means his convenient 200-meter school commute will turn into a 2-kilometer journey to a neighboring village. “My father will have to take me to school on his bicycle. The problem is he is not always free,” the child laments. Many families worry that longer distances and unsafe travel routes will deter young children – especially girls – from attending school, undermining the very goal of universal education. Critics argue that instead of closing local schools, the government should invest more in them. They point to extensive research and data showing that adequate public expenditure on education is crucial for reducing dropouts, improving learning outcomes, and uplifting disadvantaged communities. This article examines the UP school merger in the broader context of public education spending, school dropouts, and social impact, drawing on major reports and statistics since 2015. It highlights how cutting back on neighborhood schools could increase dropout rates, inequality, and unemployment, and contrasts this with examples of how strong public investment in education has benefited societies in India and around the world.

Public Education Spending: India vs. the World

Education experts have long emphasized that robust public spending on schooling is an investment in human development. International benchmarks (such as the Education 2030 Framework for Action) recommend allocating 4–6% of GDP and 15–20% of total government expenditure to education. How does India measure up to these standards, and what are the global trends?

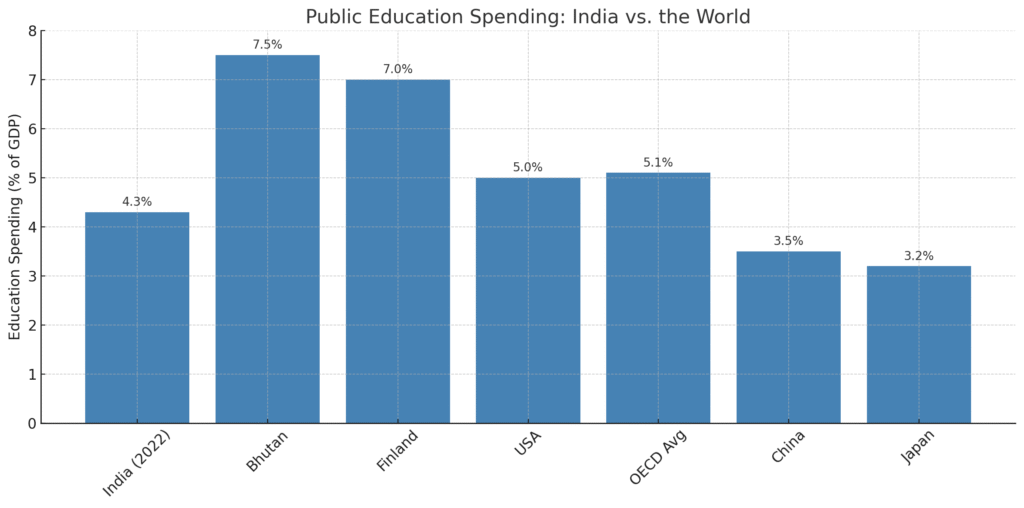

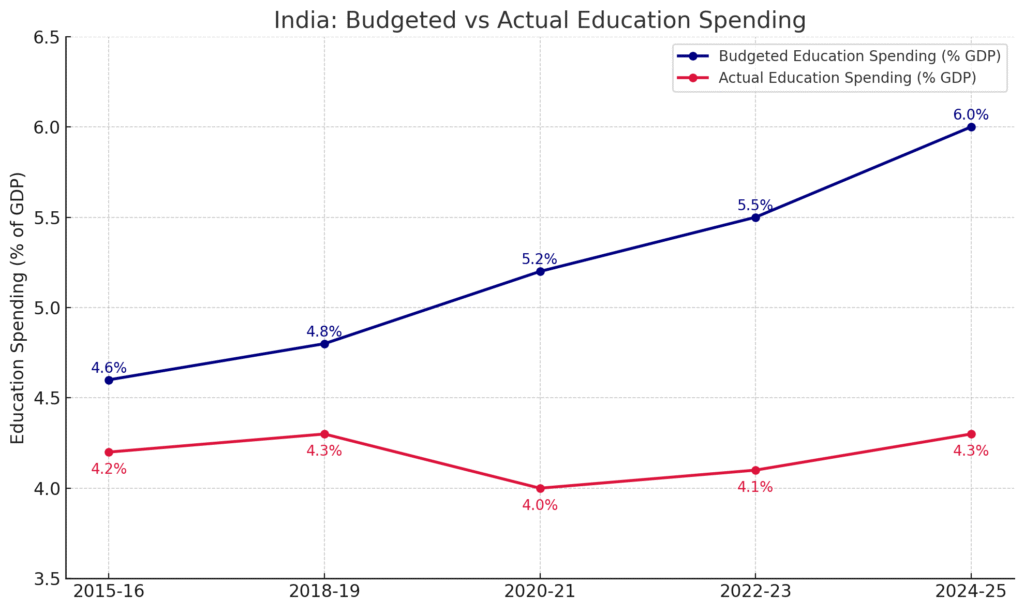

According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, India’s government expenditure on education has ranged between 4.1% and 4.6% of GDP from 2015 to 2024, which nominally meets the global guideline (4–6%). In 2022, India’s education spending as GDP share was higher than that of China and Japan, and in South Asia it was surpassed only by countries like Bhutan (7.5% of GDP). India also devoted about 13.5%–17.2% of its total public spending to education in recent years, approaching the international target of 15–20%. By these measures, Indian spending might appear adequate or even “in line with global benchmarks”.

Yet, other official analyses paint a more cautionary picture. The Government of India’s Economic Survey 2019-20 reported that India spent only 3.1% of GDP on education in 2019-20, far below the 6% goal set by every National Education Policy since 1968. In absolute terms, about ₹6.43 lakh crore (₹6.43 trillion) of public funds were spent on education in 2019-20. While this spending has increased in raw numbers over time, it has stagnated around 10–11% of total government expenditure and under 3.5% of GDP for many years. Moreover, the global average of education spending has been declining in recent years, meaning many countries are struggling to maintain investment in education.

Developed nations generally invest a higher share: for instance, the OECD countries average around 4–5% of GDP on school and college education, and some high achievers invest well above 6%. Notably, small countries with strong education outcomes often spend heavily – e.g. Finland routinely spends ~7% of GDP on education and has virtually eliminated primary dropouts. In contrast, India’s spending level, hovering around 3–4%, is often deemed insufficient given the massive scale of its school system and the learning gaps to be bridged. The NEP 2020 once again reiterated a target of 6% of GDP for education, but actual budgets have yet to reach that ambition.

It is important to note that public education expenditure directly correlates with educational outcomes and broader development. As the World Bank and UNESCO have documented, countries that sustained higher investment in schooling over past decades reaped rewards in literacy, skills, and economic growth. For example, South Korea in the 1960s–1980s dramatically expanded public schooling, achieving near-universal secondary education and later becoming a high-income economy. On the other hand, countries with chronically low education budgets often see stagnating literacy and human development indices. A recent study of five ASEAN countries confirms that government expenditure on education has a significant positive impact on the Human Development Index (HDI) – more so than even health spending in some cases. In other words, spending on schools is not a charity cost, but a strategic investment that yields high social returns. This is corroborated by research in the United States: increases in per-pupil spending have been linked to higher graduation rates, better earnings, and lower poverty in adulthood. One influential longitudinal study found that a 10% increase in school spending each year for all 12 years of schooling led to 7% higher wages and a 3 percentage-point reduction in adult poverty rates for those students. Returns are especially large for low-income students, who on average completed six more months of schooling and earned 13% higher wages when their schools received sustained funding boosts. These findings underscore that how a society funds its schools can literally shape its future workforce and economic well-being.

In India’s case, inadequate public funding often translates to shortages of teachers, poor infrastructure, and weak support services in government schools, which in turn affect student retention and learning. UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring reports have lauded India for maintaining education spending even during global downturns. But they also highlight challenges such as declining learning outcomes and persistent out-of-school pockets, indicating that money needs to be better targeted and likely increased to ensure quality education for all.

State Variations in Education Expenditure

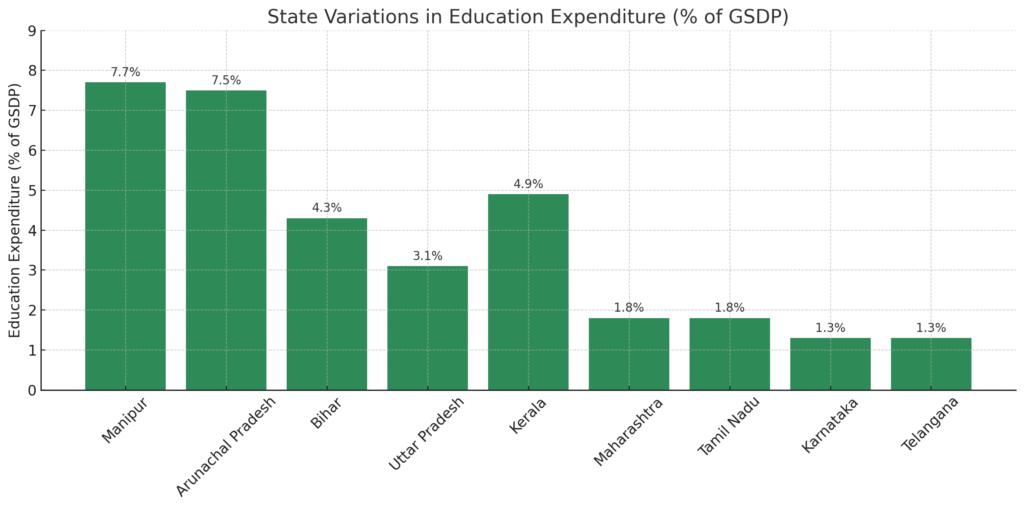

While discussing India’s public education spending, it is crucial to recognize that India’s states shoulder the lion’s share of this expenditure. Education is a concurrent responsibility, but in practice states finance the bulk of school education costs. In 2022-23, nearly 89% of total public expenditure on education in India was borne by state governments, with the central government contributing only about 11% (mostly via programs like Samagra Shiksha, mid-day meals, etc.). This means the commitment and capacity of each state significantly influence educational outcomes. There are wide disparities across states in how much they spend on education, both in absolute terms and relative to their resources.

For instance, some smaller or economically weaker states actually spend a larger share of their income on education than richer states. In 2023-24, Manipur allocated about 7.7% of its Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) to education – the highest in the country – followed by Arunachal Pradesh at 7.5%. On the other end, affluent states like Telangana and Karnataka spent only around 1.3% of GSDP on education, the lowest in India. This suggests that states prioritize differently: some put education at the forefront of public spending, while others invest relatively less (possibly banking on private sector provisioning or focusing on other sectors).

Another way to compare is the share of the state’s budget devoted to education. On average, Indian states allocate roughly 15% of their total budgets to education. But again, there is variation. According to a recent analysis by PRS Legislative Research, Uttar Pradesh has allocated about 13.8% of its state expenditure on education in 2025-26, which is lower than the average of 15% (in 2024-25) for all states. In contrast, some states like Bihar and Maharashtra have historically spent around 15% or more of their budget on education. West Bengal was noted to be on the lower side with only ~12% of its spending on education. Intriguingly, Bihar, one of India’s poorest states, spent about 4.3% of its GSDP on education in 2017-18 – the highest that year – whereas Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu spent only 1.8% of GSDP* on education, despite their wealth. This reflects a policy choice: Bihar’s heavy spending helped it achieve near-universal primary enrollment, though learning quality remains an issue, while richer states rely more on private schooling and thus spend a smaller fraction publicly.

What about Uttar Pradesh specifically? UP is India’s most populous state and has a huge school system (over 240,000 schools including all managements) to fund. In 2023, the UP government presented an ₹8.08 lakh crore budget, out of which about ₹1.06 lakh crore (13%) was earmarked for education. This included investments in primary and higher education. While ₹1 lakh crore is substantial in absolute terms, UP’s education budget as a share of its total outlay has been slightly below the national average. It indicates that UP might be under-investing relative to the scale of its needs, given its large number of rural schools and underprivileged students. Indeed, UP’s move to merge small schools can be seen as a cost-saving measure – an attempt to make do with limited resources by consolidating infrastructure and staff. The concern, however, is that saving money in the short run could undermine access for the poorest children, as discussed later.

It is worth noting that states that have consistently invested in public education have reaped social benefits. Kerala is a prime example: the state historically spent generously on education (over 5% of state GDP on average in the 1960s–80s per some analyses) and built a wide network of schools, including government-aided ones. Today, Kerala boasts India’s highest literacy rate (96.2%) and near-universal school attendance, and its human development indicators rival middle-income countries. Himachal Pradesh is another success story – despite being a hill state, it achieved literacy and schooling levels on par with Kerala by the 2000s, thanks in part to a strong government school system that reached remote villages. In contrast, states that historically lagged in school funding, like Rajasthan or Uttar Pradesh, struggled with high dropout rates and gender gaps until targeted interventions were made. Rajasthan, for instance, had very low female literacy mid-20th century; only after programs like Lok Jumbish and increased school investment in the 1990s did its female enrollment and literacy improve significantly (female literacy rose from 20% in 1991 to 52% by 2011). The lesson is clear: public expenditure effort often determines educational equity across states. Poorer regions rely overwhelmingly on government schools; if those schools are not adequately funded or accessible, children are left behind.

Public vs Private Schools: Outcomes and Dropouts

One dimension of India’s education landscape is the mix of government and private schools. About 54% of Indian students study in government institutions, while the rest attend private schools (unaided or aided). In recent decades, there was a surge in private school enrollment as some parents perceived better quality there. Yet, during the COVID-19 pandemic, that trend reversed slightly – private school enrollments fell by over 7% in 2021-22, with many students shifting back to free government schools due to economic distress.

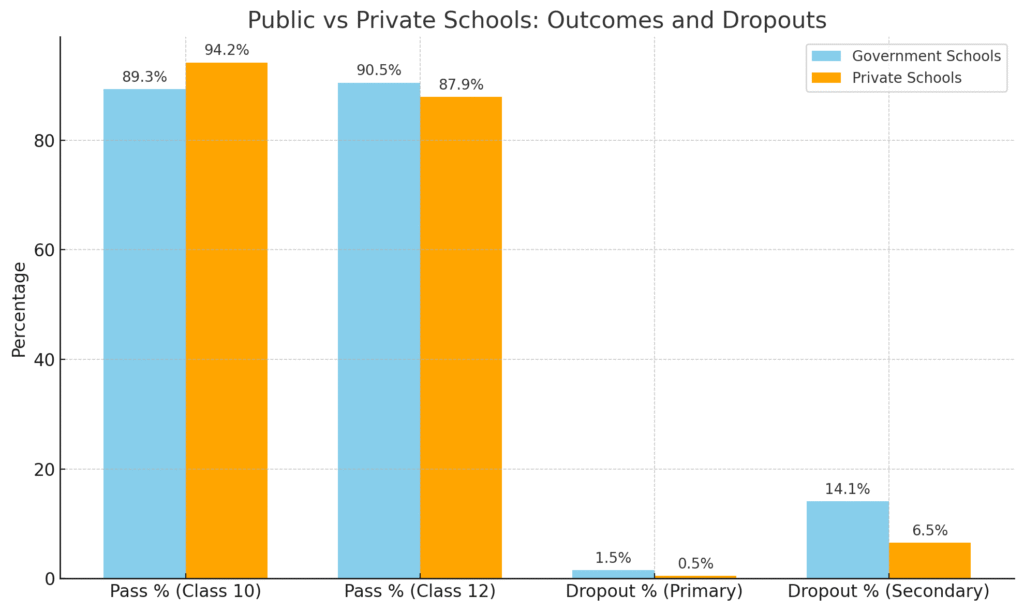

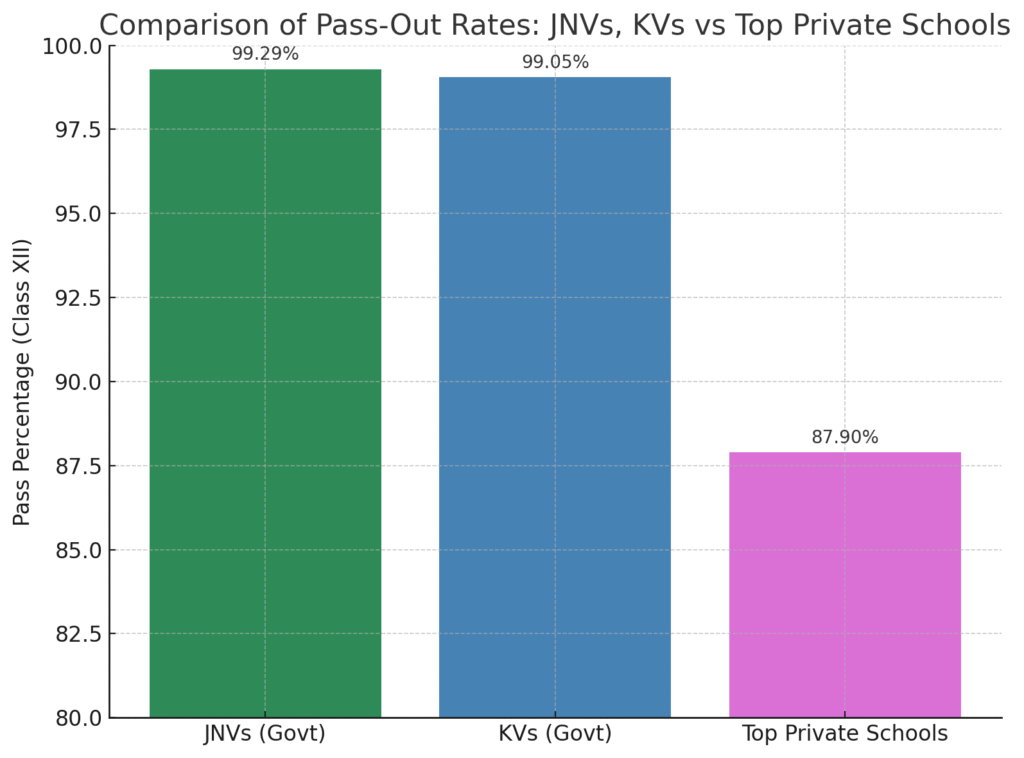

How do government schools compare to private schools in outcomes? The answer is nuanced. It is often assumed that private schools perform better, but national data and exam results show a mixed picture. In fact, in recent CBSE board examinations, the best results have come from central government-run schools. The Kendriya Vidyalayas (KVs) – a network of government schools for central employees’ children – and the Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas (JNVs) – selective rural residential schools – consistently achieve near-perfect pass rates. In 2025, JNVs and KVs achieved Class XII pass percentages of 99.29% and 99.05%, respectively, outperforming not only state government schools but even private schools. By contrast, the average pass rate in private unaided (“independent”) schools was 87.9% that year, significantly lower than the KVs/JNVs, and even slightly lower than the average 90.5% pass rate in regular government schools (many of which cater to disadvantaged students). At Class X level too, JNVs and KVs topped with ~99.5% pass rates, whereas state government schools averaged 89.3% and private schools 94.2%. These statistics illustrate that well-resourced public schools can deliver excellent results, debunking the notion that private schools are inherently superior. The elite public institutions like KVs benefit from better funding, infrastructure, and teacher recruitment, which translate into high performance.

Of course, one must account for selection effects – KVs/JNVs have motivated students and parents. But even comparing broader systems, Delhi’s government schools have shown remarkable improvement after increased investment and reforms. In 2023-24, Delhi’s state-run schools achieved a 96.99% Class XII pass rate, exceeding the national CBSE average (87.93%) and nearly matching Delhi’s private schools. Over 300 Delhi government schools had a 100% pass rate and hundreds more had above 90% results. This success followed years of the Delhi government allocating 20-25% of its budget to education – revamping infrastructure, training teachers, and introducing innovations like a “Happiness Curriculum.” The Delhi example is essentially a case study in how public expenditure and political will can turn around a struggling school system to the point where it rivals private schools in outcomes.

When it comes to school dropout rates, socio-economic factors are the key driver, but the type of school (government vs private) also has an influence. Government schools predominantly serve children from poorer and rural families, who are at higher risk of dropping out due to poverty, household responsibilities, or lack of academic support. In contrast, private school students usually come from somewhat better-off families that can afford fees and are more likely to keep their children in school through secondary stage. Thus, aggregate dropout statistics often reflect higher attrition in the government school segment, largely because of the vulnerable population they serve. A 2021 demographic study found that, after controlling for other factors, the risk of dropping out was about 50% lower for a child in a private school compared to a government school in India. This doesn’t necessarily mean the private school is better – it could be that the family’s socio-economic status is the decisive factor – but it signals that public schools need extra support to retain their at-risk students.

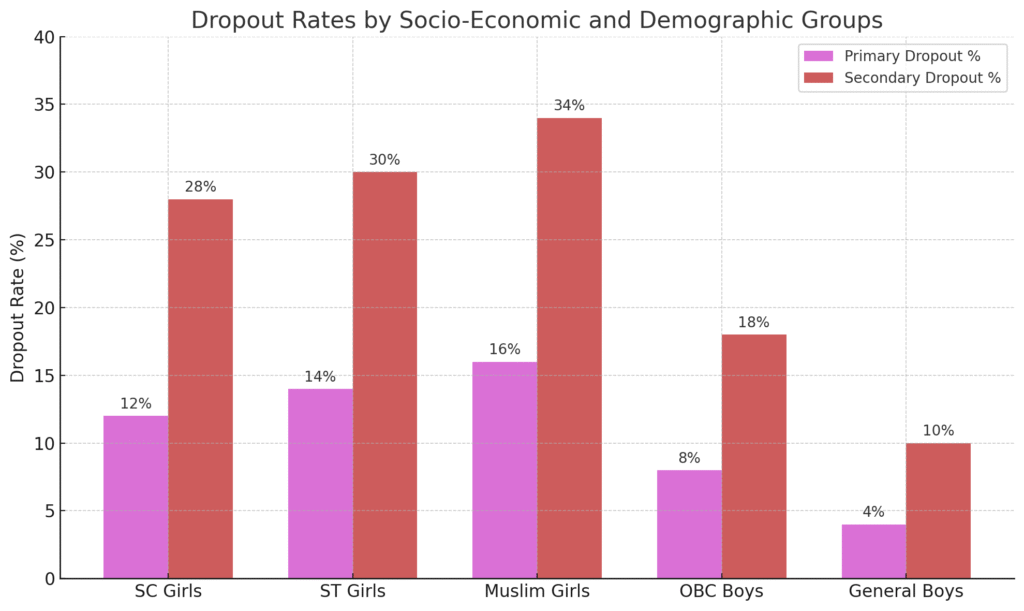

The overall dropout rates in India have been declining in recent years, which is a positive trend. According to the latest UDISE+ (Unified District Information System for Education) data, the annual dropout rate at primary level was only 1.5% in 2021-22, down from 4-5% in the early 2000s. At upper-primary (middle school), it stood around 3-5%, and at secondary (Class 9-10) about 12-14%. The Economic Survey 2024-25 confirms dropout rates of 1.9% (primary), 5.2% (upper primary) and 14.1% (secondary), showing steady improvement. However, these are averages. Certain states and demographics see much higher dropouts. For example, UDISE+ data showed Assam, Bihar, Gujarat, Karnataka with secondary dropout rates in the 15–20% range in 2021-22. Girls and boys have different reasons for dropping out: by official data, boys slightly edge out girls in overall dropout rate (e.g. 13.0% vs 12.3% at secondary), often leaving to work or due to disinterest. Girls, on the other hand, face unique barriers – many drop out due to early marriage, domestic duties, or safety concerns, especially after puberty.

Crucially, studies find that distance to school is a significant barrier, particularly for girls’ education. A 2024 study “Educating the Girl Child” found that school distance and unaffordability were major reasons for girls dropping out, in addition to household chores. When neighborhood primary schools are closed or merged, young children may have to travel much farther. Under the Right to Education (RTE) Act, primary schools are meant to be within 1 km of habitations – a norm that the UP merger policy could violate in spirit if not letter. Families may feel unsafe sending little children across 2–3 km of fields or busy roads, and in rural India there is seldom free transport. Girls are especially vulnerable – parents often pull adolescent girls out of school if the only option is a distant school involving long travel due to concerns about safety and modesty. Indeed, states that have provided bicycles or transport for girls (like Bihar’s Mukhyamantri Cycle Yojana) have seen improved secondary attendance, underlining how physical access can make or break a girl’s education. In UP’s case, critics have demanded transportation facilities for children in remote areas being affected by school consolidation. Without such support, there is a real fear that merging small schools will inadvertently raise the dropout rate among the poorest rural kids, undoing years of progress. As one petition against the policy warned, “hundreds of government schools would be shut and thousands of primary students would be out of school” if the plan proceeds without safeguards.

Beyond distance, quality differences and perceptions also affect dropout. Many parents withdraw children from government schools if they perceive the quality is poor, either abandoning schooling or trying a budget private school. Public schools often suffer from teacher vacancies, multigrade classes, and inadequate facilities in remote areas. If consolidation leads to larger, better-resourced schools, it could improve quality – but only if students actually make it to those schools. Otherwise, the risk is that smaller villages lose their local school and some children simply never re-enroll elsewhere, swelling the ranks of out-of-school youth. This outcome would be disastrous for a state like UP, which already saw a sharp post-pandemic drop in enrollments (government school enrolment fell from 1.92 crore in 2022-23 to 1.48 crore in 2024-25, and down further to ~1.0 crore in 2025-26 as per official figures). Such a steep decline suggests many children have shifted to private schools or dropped out during COVID and didn’t return. The pairing scheme is partly a reaction to these emptying schools, but unless enrollment is actively boosted, merging schools might accelerate the decline.

Socio-Economic and Demographic Impact

Access to education in India is closely intertwined with socio-economic and demographic factors – poverty, caste, gender, and religion all influence who stays in school. Public expenditure decisions can therefore have an outsized impact on equity and social justice. Well-funded public schools act as great equalizers by providing quality education to marginalized groups. Conversely, if public schools are neglected or shut down, it is the poor, rural, lower-caste, and minority communities that suffer most, as they have fewer alternatives.

Let’s consider the socio-religious profile of those most at risk. Government data and independent surveys show that children from Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), and Muslim communities often have higher dropout rates and lower educational attainment. For example, a national survey by NCPCR in 2018-19 found 39.4% of girls aged 15–18 from all communities were not attending any educational institution, and the majority of these girls were from disadvantaged castes or tribes. The Financial Express report on girls’ education noted that in states like Bihar and Gujarat, over half of dropped-out girls belonged to SC/ST communities. These are precisely the groups who rely on the government school network, since private schools may be geographically or financially out of reach for them. If those local government schools vanish, an entire generation of already-marginalized children could be denied their chance at schooling. As one analysis put it, “public education is extremely critical for social justice… ensuring it is accessible to everyone is key to building democracy”.

Religious minorities like Muslims have historically had lower female literacy rates and often fewer educational facilities in their localities. Any retrenchment of government schooling in minority-dominated rural pockets could further widen the community-wise education gap. Similarly, children from OBC and Dalit backgrounds often face social barriers; a welcoming neighborhood school with inclusive atmosphere can help overcome those, but having to go to a distant school might expose them to discrimination or demotivate them amid unfamiliar peers. These subtleties of social demography underscore why “one-size-fits-all” efficiency reforms in education can have unintended regressive effects if not carefully managed.

Another concern is the long-term impact on unemployment and illiteracy. India already struggles with a large number of youth who have incomplete education and thus limited job prospects. The unemployment rate among those with only primary or middle-school education is quite high, as they lack vocational skills for quality jobs. By contrast, completing secondary education significantly improves employability and earning potential. Thus, if policy changes like the UP merger result in more adolescents dropping out after primary or middle school, it could increase the pool of semi-educated, unemployed youth, especially in rural areas. This is not just a personal setback for them, but a loss of human capital for the economy. Every additional year of schooling is estimated to raise a person’s wages by 8-10% on average globally. At a societal level, higher education levels are linked to greater workforce productivity and innovation. Therefore, cutting back on public education investment can be economically myopic – in the long run it may undermine growth and perpetuate poverty, whereas spending on education yields returns in the form of a more skilled workforce (often calculated as a 1:2 benefit-cost ratio in advanced economies).

India’s Human Development Index (HDI) ranking has been relatively low partly because of the education component (mean years of schooling). Studies of Indian states show a clear positive link between social sector spending and HDI improvements. States that invested more in education and health (like Kerala) score much higher on HDI than those that didn’t (like UP or Bihar historically). If UP wants to improve its HDI and employment outcomes, it arguably needs more schools and teachers, not fewer. Merging schools might make administrative sense on paper if enrollments have fallen, but it does not address why they fell or how to bring children back. Critics argue that instead of closing schools, the government should tackle the root causes of low enrollment – for example, by hiring teachers to improve quality, providing scholarships or midday meals to attract poor students, starting pre-primary “Bal Vatikas” (which the UP government coincidentally plans to do) to build habit from early age, and running community campaigns on the importance of education.

Case Studies: The Power of Public Education Investment

To further illustrate how public expenditure on education can transform societies, it is useful to look at a few case studies, both global and within India.

Global Case Studies

1. Indonesia’s School Expansion (1970s): In the 1970s, Indonesia launched a massive program (SD INPRES) to build 61,000 primary schools across the country. This investment in access led to a leap in enrollment. A famous study by economist Esther Duflo found that children who benefited from the new schools gained an extra 2.8 years of education on average and 8% higher wages in adulthood compared to those who didn’t. This demonstrated how building schools (and hiring teachers) in underserved areas can boost human capital and incomes in the long term. Indonesia’s primary enrollment rate today exceeds 95%, up from around 70% before the reforms.

2. Brazil’s Bolsa Familia (2003–present): Brazil tackled dropout and poverty simultaneously by introducing a conditional cash transfer: poor families receive cash stipends if their children attend school regularly. This is a form of public expenditure (about 0.5% of GDP) targeted at education. The result was a significant increase in attendance and progression rates, especially in the poor northeast. Brazil’s secondary school net attendance rose from 65% to 85% in about 15 years, and child labor fell, partly credited to this scheme (alongside school construction). This case shows that smart spending – even if not directly on schools but on incentives – can improve educational outcomes and eventually employment prospects by keeping kids in class.

3. Sub-Saharan Africa’s Free Primary Education: Around the year 2000, many African countries (e.g. Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda) abolished tuition fees in public primary schools as part of the global “Education for All” drive, and concurrently ramped up education budgets to hire more teachers and build classrooms. The impact was immediate: Kenya, for example, saw primary gross enrollment jump from 88% in 2002 to 104% by 2003 (bringing in over a million extra children). There were challenges with quality due to the sudden influx, but overall literacy improved and a culture of schooling set in. It underlined that financial barriers are often what keep the poorest children out, and public funding to remove those barriers (free schooling, more schools) can dramatically reduce dropout and illiteracy. Today, Kenya’s youth literacy is above 87%, a marked improvement from the 1980s.

4. Finland’s Education Success: Finland is often cited for having one of the world’s best school systems. What’s less discussed is Finland’s very high public expenditure on education – around 7% of GDP – and the strong welfare state support for every child. Teachers are highly paid and respected (all public employees), and every school – even the smallest village school – is well-equipped. Finland resisted closing down small community schools for a long time to ensure education is local and inclusive. Even as some consolidations happened for demographic reasons, the government provided transport and maintained low student-teacher ratios. The outcome has been top-tier performance in international assessments (PISA) and nearly nonexistent dropout rates. By age 25, practically all Finns have completed upper secondary education, a testament to a system that prioritizes education in budgets and practice.

These cases from different contexts reinforce that public investment and policies matter enormously. Where governments have chosen to invest in building schools, subsidizing attendance, or maintaining access, they have seen more children stay in school and contribute productively later. Cutting budgets or access, conversely, tends to hurt the poorest most and can reverse gains.

Indian Case Studies

1. Kerala vs. Bihar – A Tale of Two States: Kerala, as noted, pursued a high-investment, community-based education model since the 1960s. Nearly every village in Kerala had a primary school (often aided by government funds but run by local bodies or churches) by the 1980s. Even at low per-capita income levels, Kerala spent 5%+ of state GDP on education, believing that an educated populace is the foundation for development. The result: Kerala’s literacy is 94% (female literacy ~92%), and it achieved an HDI of 0.779, the highest in India, with low unemployment relative to other states. In contrast, Bihar for many years struggled with insufficient schools and teachers. Until the 1990s, many habitations in Bihar did not have easy access to a school, and female literacy was below 25%. However, in the 2000s, Bihar increased its education budget substantially (15-20% of total spending) and hired over 100,000 contract teachers to staff primary schools in every panchayat. It also launched schemes like bicycles for girls and uniforms for all poor students. These measures paid off – Bihar’s elementary school enrollment surged and its female literacy more than doubled from 33% in 2001 to 56% by 2011. While learning outcomes still lag, the access has improved drastically due to public expenditure efforts. The comparison shows how a laggard state can catch up by making education a budget priority, and conversely how sustaining that priority is essential to not fall behind again.

2. Delhi’s Education Reform (2015–present): We discussed Delhi’s improved exam results earlier. The Delhi government’s overhaul since 2015 is essentially a case study. They doubled the education budget in a few years, now allocating about 25% of the state budget to education. This money went into repairing dilapidated school buildings, building new classrooms (to eliminate overcrowding and odd shifts), setting up modern facilities like science labs and CCTVs for safety, and most importantly, training teachers and principals (even sending them to IIMs and overseas for workshops). They also introduced curriculum innovations (Happiness Curriculum for mental well-being, Entrepreneurship Curriculum for skills). As a result, student attendance and retention improved. The government schools’ image changed so much that enrollment in Delhi government schools increased by over 100,000 in five years, reversing a prior decline, as even middle-class families started trusting the public system. This is a powerful example of how political will and increased expenditure can rejuvenate public schools, benefiting thousands of students who cannot afford elite private education. With better support, these students are now performing on par with their peers elsewhere, and will likely have better job prospects than they would have otherwise. Delhi’s model is being looked at by other states as a blueprint.

3. Himachal Pradesh’s School Outreach: Himachal Pradesh, a hilly state, achieved near-universal primary education by the 1990s despite geographical challenges. The government there followed a policy of opening a primary school within every 1–2 kilometers, even in sparsely populated mountain hamlets. This meant many small schools, sometimes with single teachers. It was resource-intensive, but it ensured easy access – no child had to walk more than 30 minutes to school even in difficult terrain. The state coupled this with community mobilization to send children to school. Himachal consistently spent a healthy share of its budget on education (around 15% or more). Over time, the investment yielded results: by 2011, Himachal’s literacy rate reached 83% (second only to Kerala) and it topped India’s education development index. Dropout rates in Himachal are among the lowest – UDISE+ 2021-22 showed its secondary dropout at just 1.5%, versus the national 12.6%. Himachal’s case underscores that for difficult regions or communities, bringing schools as close as possible to children – even at higher per-student cost – is vital for retention. It stands in stark contrast to the idea of shutting small schools; Himachal actually did the opposite for decades and reaped social gains.

4. Rajasthan’s Female Education Initiatives: Rajasthan historically had one of the worst gender gaps in education. To address this, over the last 20 years the state (often with central schemes) invested in opening residential schools for girls (Kasturba Gandhi Balika Vidyalayas) in educationally backward blocks, and recruiting local female teachers and para-teachers to make villages more comfortable sending girls to school. Projects like Lok Jumbish (People’s Movement for Education) in the 1990s, funded by government and donors, constructed schools in remote hamlets and encouraged community involvement. As a result, female enrollment improved and dropout of girls decreased. The recent data show Rajasthan’s upper-primary dropout for girls is now around 3.2% (close to the national average) whereas it used to be in double digits in early 2000s. This indicates that targeted public spending – whether on infrastructure, incentives, or staff – can overcome deep-seated social barriers.

These case studies, both international and Indian, converge on a key message: public expenditure on education, if used wisely, has a profound impact on enrollment, retention, and the long-term well-being of society. They also warn that retrenchment or neglect in this sector can cause backsliding. The UP government’s decision must be viewed in this light – will it truly improve quality without hurting access? The official rationale is that by merging schools, the state can provide better facilities (like ICT labs, libraries, more teachers) in fewer centers, thereby improving quality and even reducing dropouts through peer learning. Indeed, UP’s Additional Chief Secretary of Education argued that combining small schools will create a richer academic environment and that larger class sizes with more teachers could reduce dropouts. The High Court, in allowing the policy, also noted that scattered resources in tiny schools were depriving children of libraries, sports and digital facilities, so consolidation aims to give “quality education and equal opportunities” to all students.

However, the counterargument backed by data and ground reality is that those benefits will only accrue if students actually make it to the merged schools. If the distance or other inconveniences discourage attendance, the policy could backfire and increase dropouts, especially among the poorest. As seen in other contexts, when a local school closes, some children – often girls or the very poor – simply fall out of the system. In UP, petitioners cited RTE norms and Article 21A (right to education) concerns, fearing the pairing scheme violates the spirit of ensuring a neighborhood school within reach. The court noted the RTE Act allows flexibility if facilities are provided. Thus, the onus is now on the UP government to mitigate the downsides: perhaps by providing free transportation, hostel facilities for far-flung students, or multi-grade teaching at one campus so siblings can go together. If these are not done, critics may be proven right in a few years when we measure enrollments and dropouts.

Conclusion

The case of Uttar Pradesh’s primary school mergers highlights a broader theme in education policy: the tension between efficiency and equity. While optimizing resources is important, it cannot come at the cost of access for the last-mile student. The evidence from India and across the world is unequivocal that public investment in schooling yields rich dividends – in lower dropout rates, higher literacy, better employment outcomes, and improved quality of life. Conversely, under-investment or ill-conceived cutbacks in public education disproportionately harm the most vulnerable sections of society, widening social inequalities.

UP’s decision, coming in the aftermath of a pandemic that already set back learning for millions of children, has raised alarm because it seems to prioritize administrative efficiency over the needs of poor rural children who depend on a nearby government school. The criticism is not merely emotional but data-driven: research shows distance to school and lack of facilities are major drivers of dropouts among disadvantaged groups, and UP’s own enrollment numbers have been falling worryingly. If the state does not pair the merger with strong supportive measures (like transport and guaranteed infrastructure upgrades), it risks undermining its stated goal of improving education quality.

In a country where over 24.8 crore (248 million) students attend school and half of them rely on government schools, public education must remain a priority. It is heartening that India’s overall dropout rates are at historic lows and that governments acknowledge education as a “foundational pillar of development”. But policies like the UP school merger must be carefully implemented to ensure we do not reverse those gains. Instead of viewing small schools as a liability, an alternative approach could be to convert them into multi-grade learning centers with added pre-school sections (Bal Vatikas) – which UP also plans as part of NEP 2020 rollout – so that they become feeder centers preparing children who can then transition to larger schools for upper primary. This way, the local presence is maintained while still leveraging resource-sharing.

Ultimately, the critique of UP’s move is a call for greater public commitment to education, not less. The merger may save some money, but at what cost? If even one child drops out because her village school closed, the policy would have failed that child’s constitutional right. And if hundreds or thousands drop out, it would be a setback for society that no short-term savings can justify. On the other hand, if done with care, the reform could potentially improve schooling if every child is supported to attend the new paired schools that are better equipped. The difference lies in the public expenditure choices made alongside this decision. Will UP invest in buses, more teachers, and infrastructure to truly make consolidated schools attractive and accessible? Or will it simply merge schools to trim budgets?

The stakes are high, as education is not just another department – it is the bedrock on which the future of millions of children and the progress of the nation rests. As the data and case studies in this article have shown, there is no shortcut to quality universal education – it requires sustained public funding and inclusive policies. India’s comparison with global trends indicates we should be spending more, not less, on our schools, and directing those funds to where they are needed most. The UP school merger controversy, therefore, is more than a local administrative tweak; it encapsulates the crucial question of our times: will we invest in our human capital or short-change it? The answer will shape India’s developmental trajectory for decades to come.

Sources:

Official Government Reports and Surveys

- Economic Survey 2024-25, Ministry of Finance

https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey/ - UDISE+ 2021-22: Unified District Information System for Education

https://udiseplus.gov.in/ - National Education Policy 2020, Ministry of Education

https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NEP_Final_English_0.pdf - NSS 75th Round: Household Social Consumption on Education (2017-18), Ministry of Statistics

http://mospi.nic.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/KI_Education_75th_Final.pdf - India Human Development Survey (IHDS-II), NCAER & University of Maryland

https://ihds.umd.edu/ - State-wise Education Budget Analysis, PRS Legislative Research

https://prsindia.org/ - Budget at a Glance (Union Budget 2024-25), Ministry of Finance

https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/ - Right to Education Act (2009)

https://legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/A2009-35.pdf

News Articles and Media Reports

- UP School Merger: Explained, Hindustan Times, 2023

https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/lucknow-news/up-govt-to-merge-schools-with-less-than-50-students-101688138384537.html - UP Govt to Merge 10,000 Schools, The Tribune (PTI), 2023

https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/uttar-pradesh/up-govt-to-merge-schools-with-less-than-50-students-536697 - High Court Upholds UP School Merger, Indian Express, 2025

https://indianexpress.com/article/education/allahabad-hc-upholds-up-govt-order-to-merge-primary-schools-9211107/ - Delhi Govt School Results Outshine Private, Indian Express, 2024

https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/delhi/delhi-govt-schools-cbse-results-class-12-8983997/ - CBSE Class 12 Results 2025: School-wise performance, Education Times (TOI)

https://educationtimes.com/article/news/108973705/cbse-class-12-results-2025-kv-jnv-outperform-private-schools - Public School Enrollment Trends, India Development Review

https://idronline.org/article/education/why-are-children-dropping-out-of-government-schools/ - Girls’ Education & Dropout Study, Financial Express, 2022

https://www.financialexpress.com/education-2/girls-education-dropout-reasons-cost-distance-safety/2540024/ - Distance a Barrier for Girls’ Education, IndiaSpend

https://www.indiaspend.com/education/girls-drop-out-of-schools-due-to-distance-cost-lack-of-safety-759926

Global Studies and International Reports

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics – Global Education Monitoring Report

https://www.unesco.org/gem-report/en - World Bank: Public Education Spending and HDI

https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/education/publication/world-development-report - OECD Education at a Glance 2023

https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/ - Esther Duflo (MIT): The Impact of School Construction in Indonesia

https://economics.mit.edu/files/2806 - Northwestern University – School Finance Reform and Adult Outcomes

https://www.nber.org/papers/w20118 - Education Budget Summary by State – Mirrority Dashboard

https://www.mirrority.com/data/education-budget-by-states-in-india - Education & HDI in ASEAN Nations, Int. J. of Social & Management Studies

https://ijsmr.in/

Sub-Saharan Africa: Free Primary Education Case Studies, UNESCO

https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000138887